For those familiar with Asterix comics, Mouans-Sartoux (FR) could be compared to a small sustainable city, surrounded by the rather unsustainable French Riviera, where it’s all about real estate interest, high pressure on land use and mass tourism.

At the core of the city’s sustainable food project Good Practice, is a canteen serving one thousand 100% organic (and mostly local meals) daily, with no cost increase.

The scheme is based on a 80% food waste reduction, the introduction of plant proteins in menus, educating children and families to healthy sustainable food and the positive effects on local agriculture.

Cities are back in control

Mouans-Sartoux’s Good Practice is a real solution within a larger political initiative; redressing the balance of political leverage on food that has enabled European cities social and economic development for centuries until regions took over and the subsequent eruption of private companies excluded cities from this preponderant role.

Thanks to outstanding programs and international bodies including the RUAF (Resource centres on Urban Agriculture and Food) Foundation, the International Urban Food Network or the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact, cities are now re-claiming their influence over food policy via initiatives like the one led by Mouans-Sartoux.

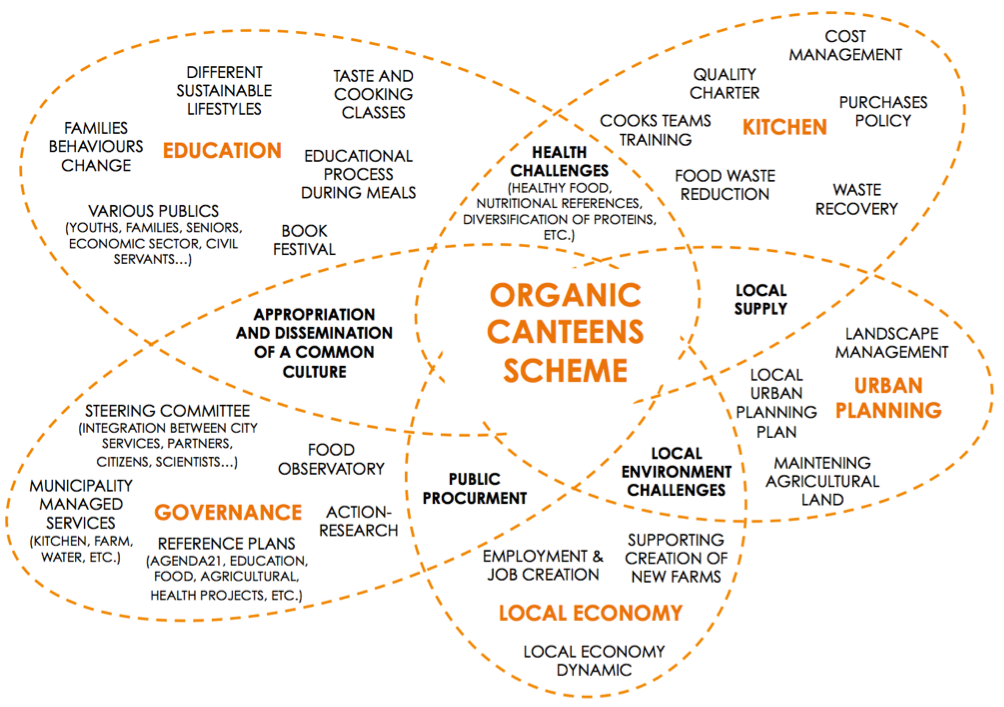

The fact that Mouans Sartoux works on the topic of sustainable food reflects a sustainable integrated approach to urban policy. It responds to a range of interrelated needs with a closely integrated response: school catering, health, employment, urban planning, agriculture, education, public procurement, environment, etc.

The biocanteens – Good practice in a nutshell

Unfortunately too often throughout Europe canteens’ meals are provided by catering services managed by large companies serving low-quality food based on ready-made products from central kitchens.

This implies limited local employment, increased transportation costs with the subsequent impact on the environment, and centralized decisions. In many European cities, collective restaurants represent an important share of the power of purchase. Cities should, with their procurement policy, facilitate a healthier public food-provisioning programme and thus influence the local agriculture development positively.

Mouans-Sartoux’s Good Practice is very well rooted into the territorial ecosystem according to the 5-leaf clover diagram above.

The canteen’s scheme in the centre is articulated in 5 key sub-systems around:

- Sustainable KITCHEN and food waste management: the shift of canteens to local and organic meals means big changes in the kitchen staff practices, for eg: training to prepare meals from scratch, cooking on demand to reduce food waste, tight coordination between kitchen staff and canteen educators watching children during meals to adjust recipes to their tastes, etc.

- Healthy food EDUCATION and sustainable behaviour change: the school’s canteen is also a complete “food school” for the children and their families, including food education during meals, choices between portion sizes to get them used to finish their plate, tasting and cooking classes, gardening activities and visits to the municipal farm. Beyond canteens, a city food and health education program aims at shifting families’ habits to local and organic food.

- Sustainable URBAN PLANNING and agricultural land use: increased synergies between the Agenda 21 (sustainable territorial plan), the local sustainable urban planning plans (called POS/PLU/PADD in the French urban planning system) and the local food health education plan (called PEL in the French urban planning system) resulted in more than 4 decades of careful urban planning, systematic acquisition of available land, concentration of urban development against urban sprawl and the creation of a municipal farm supplying the canteens.

- Food-related LOCAL ECONOMY and job creation: beyond the municipal farm, the provision of 135 hectares of municipally owned land generated the development of local agriculture, supporting with subsidies the installation of new organic farms and a potential of 50 to 100 new jobs in the sustainable food-related local economy.

- Sustainable integrated GOVERNANCE: more than 45 years of political engagement led to the establishment of consistent food territorial management and to the creation of the Centre for Sustainable Food and Education (MEAD, Maison de l’Education à l’Alimentation Durable) with 5 routes leading the city’s food and health sustainable program:

- Encouraging new agricultural settlements;

- Transformation and conservation of food;

- Raising awareness about sustainable food;

- Support for research projects;

- Communication and networking.

Think Global, Act Local – Utopia come true!

Beyond the canteen scheme and territorial food governance discussed here, the city of Mouans-Sartoux has an outstanding sustainable ecosystem. It’s a “real utopia” for André Aschieri, its former Mayor, whose inspired sustainable and integrated leadership guided the city for more than 45 years of coherent and meaningful governance.

The health and food program is integrated in all dimensions of the city from social affairs (i.e. improving the quality of local food aid, offering access to family plots or promoting the city Fair Trade label) to culture (i.e. leveraging on the yearly Book Festival to invite leading world-known figures of sustainable development such as Vandana Shiva, Pierre Rahbi, Cyril Dion, etc.) or economic development (i.e. support to the creation of complete local organic food chain).

The city of Mouans-Sartoux seems to embody the motto: ‘think global, act local’. The governance is fed and inspired by its engagement at multiple levels: regional (i.e. Agribio06, regional network of organic agriculture), national (i.e. Un Plus Bio network for quality food in canteens), European (i.e. partner in URBACT AgriUrban, hosting a National URBACT Point meeting and now Lead Partner of BIOCANTEENS) and international (i.e. founding member of the Organic Food Territories Network and partner of the Organic Food System Programmeof the FAO, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations focusing on sustainable “agri-food” systems). Equally this engagement in networks, think tanks, and conceptual, reflective projects at higher governance levels does not stay academic or hypothetical, but rather comes together, finding concrete solutions at city level.

A Good Practice that can be improved

“It’s already a 5-star restaurant” says Alicia, 10, member of the Conseil de Ville for Youth (i.e. the children city council) and pupil at Aimé Legall Primary School in Mouans-Sartoux. However, there is still scope for improvement of Good Practice such as:

- The empowerment of the kitchen staff to lead in the canteen project;

- Investigating the capacity to sustain an open food sovereignty political vision within the contrasting French Riviera context;

- The need to find new financing and secure the economic sustainability of the practice;

- The opportunity to build synergies between the URBACT Transfer Network and the recently launched University degree on “Management of Sustainable Food Projects for Territorial Administrations” and aiming to transfer Mouans-Sartoux’s Good Practice.

Transfer of Good Practices: challenges and opportunities

School canteens are a hot topic – combining aspects such as a healthy diet, the quality of food, children’s education and sustainability. It’s also a winning political hook and BIOCANTEENS therefore has a strong potential for adhesion and political support.

An enabling context: the systemic nature of the canteens scheme suggests that transferring Good Practice is highly dependent on the city’s sustainable ecosystem: it is likely to encourage partner cities to transform more than their canteens schemes stricto sensu and start an integrated sustainable territorial project likely to affect the whole city positively.

Policy creativeness: the achievements of Good Practice require partner cities to challenge public procurement rules, bend administration laws to set up a municipally-owned food chain and cope with policy innovation.

The size issue: Mouans-Sartoux is a city of 10 000 inhabitants whereas the population of all the partner cities ranges from 26 000 to 81 000 and the transfer process will have to carefully monitor this size issue – and think about how to adapt the BIOCANTEENS practices to larger contexts.

4 decades in 2 years: Mouans-Sartoux’s efforts in the last decade, its involvement in a multitude of reflective activities with its peers and the effort made building teaching modules within a University degree are clear assets to accelerate the transfer process. Nevertheless, the core characteristics of the city’s ecosystem – land management; the evolution of staff practices; change in children’s food behaviour etc. – are also the ones that take more time to evolve, limiting what is achievable in 2 years of Transfer Network.

Different levels of transfers: 6 European cities are taking part to the BIOCANTEENS Transfer Network : Pays des Condruses in Belgium; Rosignano in Italy, Trikala in Greece, Troyan in Bulgaria, Vaslui in Romania. The main challenges for them to transfer Good Practice are:

- The increase of organic food with no additional cost increase;

- The quasi-elimination of food waste;

- The shift of canteen’s staff practices;

- The development of a balanced diet and adopting healthier food habits;

- The resistance to real estate pressure, securing a provision of local agricultural land

- The stimulation of the local agriculture sector and the creation of new jobs;

- The increase of sustainable production and consumption; etc.

The strong systemic nature of the Good Practice is likely to bring about a more organic transfer with more or less important reinterpretation or translation of Good Practice into the local socio-cultural context. Developing a canteen’s scheme or changing an existing one, setting a municipally-owned food chain or leveraging the local agriculture potential, transforming public kitchen staff or orienting public procurement to shift practices of a catering provider, etc are all part of the package.

When asked in a somewhat challenging way if all Mouans-Sartoux’s wonderful achievement was true, or if it was mostly storytelling, Pierre Aschieri, the current Mayor of the city answered: “Ot’s more of a step-by-step approach where we learn by doing and progressively adjust our trajectory to arrive where we are now”.

This philosophy is certainly a good guide for the transfer cities to find their own pathway within the URBACT Transfer process!